The Union di Ladins today

Nowadays the Ladins are used to having many things: La Usc di Ladins, the use of Ladin in school and in local authorities, road signs with place names in Ladin, Ladin cultural centres, Ladin radio and Ladin TV are all commonplace, but it has taken a century to get to this point. Most of these achievements have been reached in the last 30-40 years. An idealistic group of people has worked hard for many years, with a single objective: to maintain and strengthen the Ladin identity. The Union Generela di Ladins dles Dolomites has always been at forefront of this effort, and from the start it has always had the courage to come up with ideas that were thought unnecessary or downright utopia. Much has been achieved but there is still so much to do.

Minority groups around the world all ask the same things: political and administrative unity, cultural autonomy, use of the language in education and public administration. An objective which the Ladins have still to reach is that of complete political unity, because the Ladins are divided between 3 provinces (Trento, Bozen, and Belluno) and between 2 regions (Trentino-Südtirol and Veneto). The greatest obstacle to Ladin unity is this politico-administrative division of the Ladin lands. The Ladins, unlike their German and Italian neighbours, have no cultural “hinterland” to draw upon. Everything has to be home-grown; so the laws that are made to protect the Ladin language and culture should take account of this situation, and the financial resources should be greater. The Union Generela di Ladins has the mandate to make the Ladin voice heard and demand the fundamental requirements of a minority group.

There’s an old Ladin saying which translates like this: “If you tread a well worn path, you leave no footprints”. The Union Generela di Ladins dles Dolomites has not trodden well worn paths, but has found new roads to go down, and has left its footprint on the history of the Ladins. Its voice has been strong for the Ladin minority, and will continue to be so in the future.

1905 - The Union of Ladins of Innsbruck

The best ideas for the Ladin minority and its future have often come from people abroad, and that is how the history of the Union Generela di Ladins dles Dolomites started.

Prior to 1905 a small Ladin elite had already begun to realise that they belonged to a group with different culture and language from the Germans and Italians that lived around them. Then in Innsbruck in 1905, a group of students and intellectuals from the Ladin valleys in the Dolomites joined together with the desire to maintain links with their homeland, and to demand official recognition as an ethnic group.

They called themselves the Union Ladina (in German: Ladinerverein) and in 1912 an official statute was drawn up, and they became the Union dei Ladins.

From this group came the impetus for the formation of the Union Generela di Ladins dles Dolomites, about 50 years later. The Union Generela di Ladins dles Dolomites would subsequently fight for the fundamental rights of the Ladin community, supporting and promoting the linguistic and cultural unity of the Ladins of the Dolomites.

The 1912 statute of the original group was signed by these founding members: Carl Demez, Ujep Perathoner, Father Antone Canins, Father Ojop Dasser, Father Pire Mersa, the decon, Antone Pallua and the prelate, Antone Perathoner.

Their first request regarded the official Tyrol census. They demanded that the Ladins should no longer be considered Italians, as they usually were (although 1846 and 1910 were exceptions), but as an independent group.

The objectives of the statute are clear:

- The official recognition and the unification of all the Ladins of Tyrol.

- The standardisation of the written language of all the different forms of the Ladin language.

- To found a Union of Ladins in every Ladin valley.

- To organise cultural events, to publish books of Ladin culture and literature, to produce calendars and a newspaper.

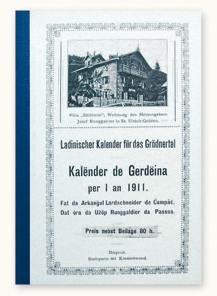

Putting this into practice proved far from simple. In 1905 “L amik di Ladins - Der Ladinerfreund” came out and 3 editions were published. In 1908 2 editions of the newspaper “Der Ladiner” appeared in Brixen. The “Kalënder de Gerdëina” (later “Calënder Ladin”) came out in 1911, and enjoyed a longer run. Meetings and events were organised. Contacts were made with the Ladins of the Grisons in Switzerland and Friuli.

However, the outbreak of WW1 in 1914 put a stop to this initial blossoming of the Ladin identity.

“Der Ladiner” (1908).

“Der Ladiner” (1908).

“Kalënder de Gerdëina” (1911).

“Kalënder de Gerdëina” (1911).

A new Union of Ladins after WW1

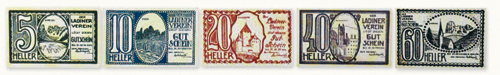

During the first world war part of the front line crossed the Ladin territories, causing great hardship in the Ladin valleys. The war ended in 1918 and the Italian troops conquered the Ladin valleys. It was a time of great uncertainty and of transition. One of the last actions of the Union of Ladins was to print vouchers to be used instead of money, a kind of temporary Ladin currency. In 1925 the Union reconfirmed its statute, giving up its political aims. It remained active in Innsbruck until 1938.

A more politicised group began to form around Leo Demez, who would later be one of the founders of the Union di Ladins de Gherdëina. This new group had links with the Deutscher Verband and aimed to proclaim Ladin ethnic independence and promote the language.

La Plié da Fodom after bombing during WW1.

La Plié da Fodom after bombing during WW1.

Vouchers worth 5, 10, 20, 40 & 60 Heller distributed by the Union dei Ladins of Innsbruck to help the Ladin population.

Vouchers worth 5, 10, 20, 40 & 60 Heller distributed by the Union dei Ladins of Innsbruck to help the Ladin population.

The Ladin flag

In the Treaty of St. Germain in 1919 the entire region, Trentino, Südtirol and all the Ladin valleys, were handed over to Italy, although no mention of the Ladins was made in the treaty.

Reaction followed on 5th May 1920 when Leo Demez and the Union di Ladins organised a rally at Jouf de Frea (the Gardena Pass) with representatives from all 5 Ladin valleys. They were protesting about their omission from the treaty and sudsequent lack of self determination.

It was at this meeting that the Ladin flag was seen for the first time. The colours are blue, white and green, symbolising the sky, the snow and the meadows and the forests.

The colours of the Ladin flag: blue for the sky, white for the snow and green for the meadows and forests.

The colours of the Ladin flag: blue for the sky, white for the snow and green for the meadows and forests.

The official colours of the ladin flag with their international codexes.

The official colours of the ladin flag with their international codexes.

The division of the Ladin territories

In the 1921 census, the Italian government allowed the Ladins to declare their status as Ladin speakers, but by 1923 the fascist government abolished this privilege.

The new regime saw the Ladins as a “grey mark which needed to be removed”.

The Ladin territories were divided into three parts. A decree of 21st January 1923 created the province of Trentino, and the communities of Anpezo, Col and La Plié da Fodom were assigned to the province of Belluno.

In another decree of 2nd January 1927, the province of Bozen was formed taking in the valleys of Badia and Gherdëina. Fascia stayed in Trentino.

This situation, with the division into three different provinces, is still in place to this day.

During the fascist regime, the Ladin flag was outlawed, and cultural groups were forbidden. Work continued, however, in silence, and people carried on gathering the ethnographic and lexical material, which would later be the foundation for the renaissance after WW2.

Hitler’s “options”

In 1939 an agreement between Hitler and Mussolini gave the inhabitants of the Ladin valleys, apart from Fascia, the option to keep their Italian citizenship or to opt for German status and be transferred to the Third Reich. In this way they were forced, which ever option they chose, to give up their true Ladin identity.

In Gherdëina 81% opted for the Reich, in Badia 31.7%, in Fodom and Col Santa Lizia 18% and in Anpezo 4%. Although Fascia was not included in the deal, there were 300 inhabitants who would have opted to re-locate.

In total there were 7,027 Ladins who chose German citizenship, although only about 2,000 were ever moved to the Reich because developments in the war changed the situation and the idea was dropped.

In 1943 the provinces of Bozen, Trento and Belluno all came under German command as the Alpenvorland territory. On the 20th September 1943 Col, Anpezo and Fodom were rejoined to the province of Bozen, while Fascia was left with Trento.

On 2nd June 1945 the arrival of the American troops signalled the end of WW2 for the Ladin valleys.

With the end of the dictatorship, the Ladins embarked on new political and cultural initiatives.

In 1939 81% of the population of Gherdëina opted for the Reich.

In 1939 81% of the population of Gherdëina opted for the Reich.

1945 - New hopes for unity

On 8th May 1945 a new movement called Zent Ladina Dolomites came into being, formed out of the Ladins who had chosen to stay with Italy (known as Da-Bleiber), with Anpezo and Fodom inhabitants at the forefront. The organization called for administrative autonomy for the Ladin valleys in the Bozen province.

On 15th June 1945 the Zent Ladina Dolomites was made official at Jouf de Frea and it began to publish the newspaper of the same name, of which there were 11 editions.

On 19th July 1945 the first meeting took place between another group of Ladins. They included Luis Trenker (1892-1990), Franz Prugger (1885-1960) and Leo Demez (1891-1978). After its official foundation on 5th August 1945 in Urtijëi, the group suffered from disagreements among the people following Hitler’s options.

However, their objectives mirr-ored those of the Union of Innsbruck of 1905:

- support and development of the Ladin language;

- support for the culture, religion, traditions and customs of the Ladins;

- support for handicrafts, industry and commerce in the Ladin valleys;

- preference for Ladins in gaining employment in local authority and education;

- the teaching of the Ladin language in school alongside German and Italian;

- general support for everything regarding the Ladin territories.

Initially the Union di Ladins de Gherdëina took its place as one of the Ladin unions which the Union of Innsbruck envisaged as existing in each Ladin valley.

In November 1945 Max Tosi (1913-1988) founded the Union Culturela di Ladins in Meran.

Its aims were purely cultural, and among its pioneering initiatives were the first radio broadcasts from Bozen in Ladin, which took to the air on 4th April 1946. A newspaper was set up, L Popul Ladin, but due to financial difficulties only came out once on 23 August 1946. These were testing times for the Unions di Ladins .

They were busy fighting for official recognition, but at the same time they had to convince the Ladin people themselves that their native tongue was worth defending, and this aspect proved far from easy. Many Ladins, including their political representatives, failed to realise the importance of teaching Ladin in school, believing the language to be inferior to Italian or German.

To tell the truth, the language had its shortcomings, in that there was no standard Ladin at that time, a pan-Ladin literary tradition had yet to be born, and the various idioms of Ladin were written with different spelling conventions. The creation of inter-Ladin partnerships proved extremely difficult. In part because of the division between the three provinces, and also because of the mistrust which had grown up amongst the people due to Hitler’s option.

The meeting at Jouf de Sela on 14th July 1946.

The meeting at Jouf de Sela on 14th July 1946.

L’Union Generela di Ladins dles Dolomites

After WW2, the Ladin unions were animated by a desire for linguistc, cultural and social identity. In July 1946 an historic meeting took place on Jouf de Sela (the Sella Pass), organised by the Zent Ladina Dolomites.

More than 3,000 people, from all the Ladin valleys came to demonstrate their unity and to claim the following rights, which are still valid today:

- the recognition of the Ladins as an ethnic group;

- the unification of all Ladins within the province of Bozen;

- a Ladin electoral constituency,

- official recognition of the Ladin language,

- schools, books and publications in Ladin;

- observance of Ladin traditions;

- an itinerant Ladin magistrate’s court;

- a tourist agency and a chamber of commerce;

- protection of Ladin emigrants;

- radio broadcasts in Ladin

- conservation of Ladin place names

The day after the meeting on Jouf de Frera, a telegram was sent to the then premier Alcide Degasperi, outlining these points, together with a request for a referendum on the Ladins of Anpezo, Fodom, Col, Fascia and Fiemme, joining the province of Bozen. The telegram was never answered.

The political wing was active for the whole of 1947, but when the first statute granting autonomy to the provinces of Trento and Bozen was approved in 1948 it became less important. In September 1946 the Union di Ladins de Gherdëina was created, and then in June 1947 there was a preliminary meeting in Predaces with a view to starting a similar group in Badia. The group formed in 1948, but had to wait until 1967 to have a statute.

In December 1947 Max Tosi moved from Meran to Bozen and founded the Union di Ladins a Bulsan. This group attracted to it the Union di Ladins de Gherdëina and the Union di Ladins dla Val Badia, forming the nucleus for the Union Generela di Ladins. On 18th April 1951 the name was officially changed from Union di Ladins to Union di Ladins dla Dolomites.

In May 1955 the Union di Ladins de Fascia came into being. In July 1957 the Union di Ladins dla Dolomites transferred its head office from Bozen to Urtijëi, and at the same time extended the name to: Union Generela di Ladins dla Dolomites.

Here are the objectives as laid down by its statute:

- to protect and develop the Ladin cultural and linguistic heritage

- to advance Ladin traditions, place names and other aspects of Ladin-ness

- to maintain and strengthen the Ladin identity in all fields, including through the mass media

- to promote collaboration between all the Ladins of the Dolomites

- to protect the interests of the Ladin population in all things cultural, social and environmental

- to strive for the rights of the Ladin group as a whole and to collaborate with the other Ladin organisations in the Grisons of Switzerland and in Friuli in Italy.

The Cësa di Ladins

In June 1951 a plot of land was obtained in Urtijëi, and work began on the Cësa di Ladins (the house of the Ladins). It was the brainchild of the Union di Ladins de Gherdëina, convinced that the Ladins needed a cultural centre. The Union Generela supported the project wholeheartedly and was involved in raising the necessary funds, going all the way to the prime minister for help.

On 1st August 1954 the centre opened to coincide with the first inter-Ladin congress. The congress was also attended by representatives from the Grisons and Friuli.

From the outset the Cësa di Ladins was the home of the Union Generela di Ladins dla Dolomites, the Union di Ladins de Gherdëina and the Museum de Gherdëina. In 1972 it also became the head office of the newspaper La Usc di Ladins.

The inauguration of the Cësa di Ladins in Urtijëi, headquarters of the Union Generela di Ladins dla Dolomites. (1954)

The inauguration of the Cësa di Ladins in Urtijëi, headquarters of the Union Generela di Ladins dla Dolomites. (1954)

The “Cësa di Ladins” today

The “Cësa di Ladins” today

1948 - The First Statute of Autonomy

The Treaty of Paris, which was ratified in 1946, after the second world war, failed to recognise the existence of a Ladin ethnic group, giving autonomy only to the German-speaking population. The first statute of autonomy was promulgated on 31st January 1948, but didn’t satisfy the German population, because the autonomous territory included Trentino, which is mainly Italian-speaking, thus putting the Germans into a minority. The Ladins gained long awaited, albeit minimal recognition as the third linguistic group in the region. Articles 2 and 87 speak of “respect for the culture, the place names and the traditions of the Ladin populations”. This small conquest, however, was overshadowed by the confirmation of the division of the Ladin lands in three provinces and two regions. Another problem which caused agitation among the Ladins in the period immediately after WW2 was the debate about the school system. The Ladin unions backed a joint system with half of the lessons in Italian and half in German, with the Ladin language to be taught as well. This joint system was applied in Badia and Gherdëina, but Fascia, in Trento province, and Fodom and Anpezo, in Belluno province, were left out.

In the province of Trento, Ladin lessons began much later, starting with the school year 1969/70. The Ladins of Belluno had to wait until 1999 for this privilege.

The Austrian minister Karl Gruber & his Italian counterpart Alcide Degasperi at the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1946).

The Austrian minister Karl Gruber & his Italian counterpart Alcide Degasperi at the signing of the Treaty of Paris (1946).

“The Committee of 19”

The statute of autonomy of 1948 was strongly contested by the German minority. The culmination of this protest was the movement known as “ Los von Trient” (away from Trento). The SVP (Südtirol People’s Party) asked Austria for help, who in turn took the question to the United Nations.

In order to settle the controversy and to take the edge off the discontent of the German group, a committee was instituted called the “Committee of 19”, and was active from 1961-1964. The committee also had a Ladin member, namely Franz Prugger, the president of the Union Generela.

The Union Generela, together with the mayors of Gherdëina and Badia, made the following demands:

- that the Ladins should be represented in the regional and provincial councils, and in the other major public bodies

- that the Ladin language should be taught as much as possible in primary schools, and that teaching should also take place through the medium of Ladin.

- that the local education authority should be adapted, with the creation of an autonomous Ladin school system, with a Ladin inspector in charge.

- the promotion of cultural and recreational activities, and the Ladin press.

The Italian president Giovanni Leone visits the Cësa di Ladins (1975)

The Italian president Giovanni Leone visits the Cësa di Ladins (1975)

The Union of all the Dolomite Ladins

In 1964 the Union Generela di Ladins became stronger with the foundation of the Union di Ladins de Fodom. Then in 1975 Ampezzo followed suit and the Union di Ladis de Anpezo was created. And so all of the Ladin valleys were united by a single cultural organisation: the Union Generela di Ladins dla Dolomites.

Representatives of the Ladin Unions with Italian president Sandro Pertini during his holiday in Gherdëina (August 1980). From left: Danilo Dezulian (+), Sergio Masarei (+), Lois Trebo, Sandro Pertini (+), Ilda Pizzinini, Gilo Prugger, Guido Insam (+) and Iji Menardi.

Representatives of the Ladin Unions with Italian president Sandro Pertini during his holiday in Gherdëina (August 1980). From left: Danilo Dezulian (+), Sergio Masarei (+), Lois Trebo, Sandro Pertini (+), Ilda Pizzinini, Gilo Prugger, Guido Insam (+) and Iji Menardi.

1972 - The Second Statute of Autonomy

The work of the Committee of 19 culminated in the 137 precepts which make up the second statute of autonomy, which was approved in 1972.

The precepts which enlarge the autonomy of the province of Bozen were largely in favour of the German population, while they regarded the Ladins of the province to a much lesser degree. Articles 19 and 102 recognise the Ladins as an ethnic group, and Ladin as a language, with a Ladin schools board, and an increase in Ladin radio and TV programmes. Only one article mentioned teaching Ladin in Fascia. The Ladin valleys were driven even further apart, and a wave of discontent began to sweep the valleys. In 1972 and 1977 the Fascia communities, backed by the Union di Ladins de Fascia, asked to transfer to the province of Bozen. In 1973 the Grop Politich Organisà Ladins (Ladin political organisation) came into being in Fascia, but had supporters also in Badia. In the same year Fodom made a request to transfer to Bozen. In order to calm the discontent in Fascia, the province of Trento gradually began to concede some rights. In 1975 the Ladin Cultural Institute “Majon di Fascegn” was founded. In 1977 nursery schools started to teach Ladin, and the Comprensorio “Ladino di Fassa” C11 was created (a separate local authority organisation). In 1976 a Ladin Insitute was created in the Bozen province, dedicated to “Micurà de Rü” (Nikolaus Bacher 1943-1993), the clergyman from San Ciascian who came up with the first system of standardised Ladin writing.

In 1983 the Union Autonimista Ladina came into being in Fassa. Its representative Ezio Anesi (1943-1993) was elected to the Trento provincial council. In 1985 a law was passed giving importance to Ladin cultural and recreational activities, and the press in Fassa. And in 1987 Ladin place names were safeguarded by another law. In March 1978 a group formed called Comunanza Ladina, which brought together Ladins who live in and around the city of Bozen, and similarly a group called Ladins Dlafora, in Brunico, which sought to help all Ladins who live outside their native valleys, but who want to maintain their Ladin identity.

The arrival of these two new groups had a political impact: in both cities, Bruneck in 1985, Bozen in 1989, Ladin candidates stood for election, resulting in the election of a Ladin to the local council. In Bozen the Consulta per i problemes Ladins was formed, which was recently renamed Consulta Ladina dl Comun de Bulsan. In Innsbruck the old Union di Ladins was re-formed, and organises regular cultural events.

The Unions di Ladins of Anpezo and Fodom obtained their first recognition from their region (Veneto) with law n. 60, which pledged financial support for their activities. In 1991 the Union Generela backed the request of these two communities to transfer to the province of Bozen. In 2004 the province of Belluno set up the Istitut Ladin “Cesa de Jan” in Col.

In the session of 9th March 1992, the SVP approved the conclusion of the conflict between Italy and Austria with the abstention of the Ladins, who never received a response to their requests.

They were:

- a representative on the provincial council, in the junta and in the joint commissions;

- an increase in the teaching of Ladin in the schools;

- a trilingual written exam for workers in offices of particular interest to the Ladins;

- the elevation of the Ladin school board to equal status with the other groups;

- doubling of TV and radio broadcasts and an autonomous staff;

- support for the Ladins in every sector.

1985 – 2000 years of Ladins

1985 was proclaimed “Year of the Ladins- 2000 years of Raetoromania” , by the Swiss Grisons and by the provinces of Trento and Bozen. The period goes back to 15 B.C., when Romans conquered the Alps thus giving rise to another neo-latin language.

The Union Generela di Ladins took the opportunity to reiterate its demands, the main ones being:

- the use of the Ladin language as administrative language

- the creation of a unified written language

- official recognition of the Ladin flag

- a modification of the proportional representation in elections in Bozen province

- more radio and TV airtime

During the convention on local autonomy organised by the Union Generela at Al Plan de Mareo, it became clear that a greater administrative autonomy was necessary.

The medal which was produced for the 2000 years of Ladins.

The medal which was produced for the 2000 years of Ladins.

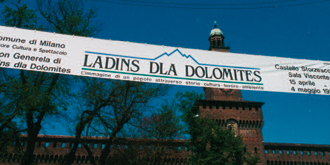

Ladin Exhibition in Milan

In 1988 the Union Generela and the various groups in the valleys organised an exhibition called “Ladins dla Dolomites” at Castel Sforzesco in Milan. The Ladin area was presented both as an ethno-cultural group, and as an economic force with reference to tourism. Many groups were involved in the exhibition, cultural and business organisations, showing the capability to collaborate despite the administrative constraints posed by the division of the Ladin territories.

The exhibition at “Castello Sforzesco” in Milan.

The exhibition at “Castello Sforzesco” in Milan.

Carlo Willeit and Ilda Pizzinini with minister on. Maccanico.

Carlo Willeit and Ilda Pizzinini with minister on. Maccanico.

Presidents of the Union Generela di Ladins dles Dolomites

Faustino Dell’Antonio, Gherdëina [1889-1975]: 1951 - 1957

Faustino Dell’Antonio, Gherdëina [1889-1975]: 1951 - 1957

Vinzenz Aldosser, Gherdëina [1901-1968]: 1957 - 1960 und 1964 - 1968

Vinzenz Aldosser, Gherdëina [1901-1968]: 1957 - 1960 und 1964 - 1968

Franz Prugger, Gherdëina [1891-1978]: 1960 - 1964

Franz Prugger, Gherdëina [1891-1978]: 1960 - 1964

Massimiliano Mazzel, Fascia [1900-1977]: 1968 - 1969

Massimiliano Mazzel, Fascia [1900-1977]: 1968 - 1969

Franz Vittur, Val Badia [1928]: 1969 - 1970

Franz Vittur, Val Badia [1928]: 1969 - 1970

Bruno Moroder, Gherdëina [1921-1982]: 1970 - 1973

Bruno Moroder, Gherdëina [1921-1982]: 1970 - 1973

Lois Trebo, Val Badia [1935]: 1973 - 1979

Lois Trebo, Val Badia [1935]: 1973 - 1979

Vigilio (Gilo) Prugger, Gherdëina [1925 - 2015]: 1979 - 1981

Vigilio (Gilo) Prugger, Gherdëina [1925 - 2015]: 1979 - 1981

Luigi (Iji) Menardi, Anpezo [1929]: 1981 - 1983

Luigi (Iji) Menardi, Anpezo [1929]: 1981 - 1983

Carlo Willeit, Val Badia [1942]: 1983 - 1986

Carlo Willeit, Val Badia [1942]: 1983 - 1986

Ilda Pizzinini, Val Badia [1934 - 2015]: 1986 - 2003

Ilda Pizzinini, Val Badia [1934 - 2015]: 1986 - 2003

Giovanni (Nani) Pellegrini, Fodom [1934]: 2003 - 2005

Giovanni (Nani) Pellegrini, Fodom [1934]: 2003 - 2005

Michil Gustav Costa, Val Badia [1961]: 2005 - 2008

Michil Gustav Costa, Val Badia [1961]: 2005 - 2008

Elsa Zardini, Anpezo [1956]: 2008 - 2015

Elsa Zardini, Anpezo [1956]: 2008 - 2015

Daria Luisa Milva Mussner, Gherdëina [1961]: 2015 - 2022

Daria Luisa Milva Mussner, Gherdëina [1961]: 2015 - 2022

Antone Pollam, Fascia [1952]: 2022 - 2023

Antone Pollam, Fascia [1952]: 2022 - 2023

Daria Luisa Milva Mussner, Gherdëina [1961]: 2023 - 2025

Daria Luisa Milva Mussner, Gherdëina [1961]: 2023 - 2025

Roland Verra, Gherdëina [1956]: 2025 -

Roland Verra, Gherdëina [1956]: 2025 -

The reasons for the ladin referendum in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Colle Santa Lucia and Livinallongo

The ladin language comes from Latin and is thus a sister language of Italian and French. Moreover, customs and traditions dating back several centuries characterise the local population and contribute to forming a small ‘nation’ in the heart of the Dolomites. The Ladin people have always lived in peace and harmony with their Italian and German-speaking neighbours. 2007, however, a lot has been said and written about the socalled ‘Ladin referendum’, held in the three municipalities of Cortina d’Ampezzo, Colle Santa Lucia and Livinallongo for a return to the province of Bolzano-Bozen. As it often happens, the information provided by the media has not always been totally objective and, therefore, we would like, and we also feel somehow obliged, to briefly explain the real reasons for the referendum. We hope that in this way we will be able to raise awareness and interest in the smallest and, at the same time, the oldest population of this corner of Italy.

There are ca. 35,000 Dolomitic Ladins living in the following five valleys around the Sella group: Badia Valley with Marebbe, Gardena Valley, Fassa with Moena, Livinallongo with Colle Santa Lucia and Cortina d’Ampezzo. The valleys were all part of Tyrol until 1919 and they were under the same administration until 1923. When our region was handed over to Italy, Ampezzo, Colle and Livinallongo as well as the other Ladin areas were all part of the newly established region of Venezia Tridentina. Hence, it was only as late as 1923 that the three municipalities were annexed to Veneto, of which Colle and Livinallongo had never been part and Cortina only between 1420 and 1511 (with the difference that the Serenissima had once respected the autonomy of Cadore, conquered by Friuli, whereas modern Veneto did not want to acknowledge any ‘diversity’ inside its borders). With the establishment of the provinces of Bolzano-Bozen and Trento in 1927 and the assigning of Fassa Valley to the latter, the partition of the Ladin population was finally completed. The declared aim of this measure was to undermine the Ladin unity. This situation of division unfortunately still persists and constitutes a threat to the survival of the Ladin group. Between 1945 and 1948 the three municipalities made several attempts to join the Ladins of the province of Bolzano-Bozen on the basis of their long common history, language affinity, culture and traditions. In those post-war years the province of Bolzano-Bozen was far from being the rich and prosperous region that it is today: the reasons for the referendum were purely historical, linguistic and cultural. Nonetheless, the possibility of a reunification was denied, although provided for by the article 132 of the Italian Constitution. With the autonomy of the provinces of Trento and Bolzano- Bozen, granted by the international agreements of Paris, the Ladin communities of these two provinces (in the valleys of Badia, Gardena and Fassa) were given some rights of vital importance to their survival: Ladin radio programmes (1946), television programmes (1988), Ladin as a subject at compulsory schools (1948), recognition of the Ladin group as a third linguistic group (1951), guaranteed political representation (1972), a Ladin provincial school authority (1975), the allocation of public posts according to the principle of ethnic quotas (1976), the use of the Ladin language in administration (1989). Although they historically belong to the same Dolomitic Ladin group, the Ladin population of the three municipalities of Ampezzo, Colle and Livinallongo were excluded from these rights, as they were and still are part of Veneto. The denial of any Ladin particularity in this region urged the three municipalities to ask for the passage to the province of Bolzano-Bozen in 1947, 1964, 1973, 1974 and 1991. The reasons for this request were still historical, linguistic and cultural, and not economic, since in the 1970s the mainly agricultural province of Bolzano- Bozen was much poorer than the industrialized region of Veneto. Their legitimate aspirations being blocked by a ‘neo-ladin’ movement artificially created by Bellunese politics at the beginning of the 1990s, the three historically Ladin municipalities asked again and finally got the opportunity to express themselves in a referendum on 28 and 29 October 2007. The result, 79.87% in favour of a passage to the province of Bolzano-Bozen, speaks by itself. Finally, after briefly going through the so-called ‘questione ladina’, we would like to stress the following five points:

- The ‘Ladin referendum’ aims at the reunification of the Ladin communities under one provincial administration (the province of Bolzano-Bozen) in order to guarantee the survival of the language. Without an appropriate protection policy the ca. 4,500 historical Ladins of the province of Belluno (not to be confused with the ca. 50,000 ‘neo-ladins’ of the areas of Cadore and Agordo who have exploited the adjective ‘Ladin’ to their own advantage and interests, often in diametrical opposition to the historical Ladins) will disappear within a few generations.

- The ‘Ladin referendum’ expresses a historical, linguistic and cultural will, not economic interests. The co-occurrence of this referendum with that of other municipalities has often led to a confusion of the reasons, but the different realities should be clearly distinguished.

- Passing to the province of Bolzano-Bozen, the three municipalities would of course still be part of Italy, so that the Republic would not be deprived of any territories or money. Only the administration of the municipalities would change (local vs. central).

- We absolutely do not want to deny Veneto or any other region the right to fiscal autonomy or legislative and/or tax policies in their favour. On the contrary, stronger local autonomies are exactly what we want to support. However, as these measures are economic and not linguistichistorical and cultural, they do not solve the problem of a Ladin unity and survival in the five valleys around the Sella group. The reunification of the Ladin communities and fiscal federalism are two different goals and we want to reach them both, not one regardless of the other.

- It is well known that unjust borders can cause problems and contentions. In the case of the Ladin communities, no national frontiers would be changed but only borders within one and the same country, according to modalities clearly provided for by the law. We are confident that the politicians, who represent the population (including numerically small ones as in the case of the Ladins), will not be against the people’s will of a reunification, clearly expressed in the plebiscite. • We are sure that you will sympathize with the legitimate aspirations of the Ladin minority to be together in the future as in the past.